Professor Inés Hernández-Ávila, a distinguished poet, translator and artist, has gained international recognition for her scholarship on the cultural and linguistic revitalization movements of Indigenous people. In keeping with the hemispheric approach of the Department of Native American Studies, where she serves on the faculty, she focuses on contemporary Indigenous literature and Indigenous religious traditions of the Americas.

Hernández-Ávila is of Niimiipuu/Nez Perce heritage, enrolled on the Colville Reservation, Washington, on her mother's side, and Tejana (and Mexican Indigenous) on her father's side. With support from the Public Impact Research Initiative, Hernández-Ávila organized a historic Niimiipuu/Nez Perce delegation to Chiapas, Mexico, in August 2021 to engage with Mayan writers, artists and community activists. In this interview, we explore Professor Hernández-Ávila's project and public scholarship.

What sparked the idea for your public impact project?

My passion, devotion and commitment are to help bring Indigenous peoples of the Americas together. The heart of this project is Indigenous language revitalization, with a focus on Niimiipuutimtki, the Nez Perce language and the Maya Tsotsil and Maya Tseltal languages of Chiapas. Niimiipuutimtki is an endangered language with only 10 fluent speakers left. My late Uncle Frank was one of those fluent speakers. I have been working in Mexico with Indigenous writers since the late 1990s, learning and observing how they strategically promote language revitalization through creative writing in Indigenous languages. In this way, Indigenous languages come out of the shadows to take a dignified place in the world of literary creation — in fact, their success is such that many of the Mayan writers in Chiapas have had their works translated into several European languages.

The more I witnessed, the more I asked myself, “What if Native people from the North could come and see how Mayan people in Chiapas are organizing around language revitalization and the promotion and production of literature in all genres?” The idea of using our languages to promote revitalization is happening some here in the U.S., but not at the level that's happening in Chiapas. My Mexican grandparents made sure that I learned Spanish when I was young, and it is serendipitous that I now travel to Mexico for research with Indigenous writers and artists.

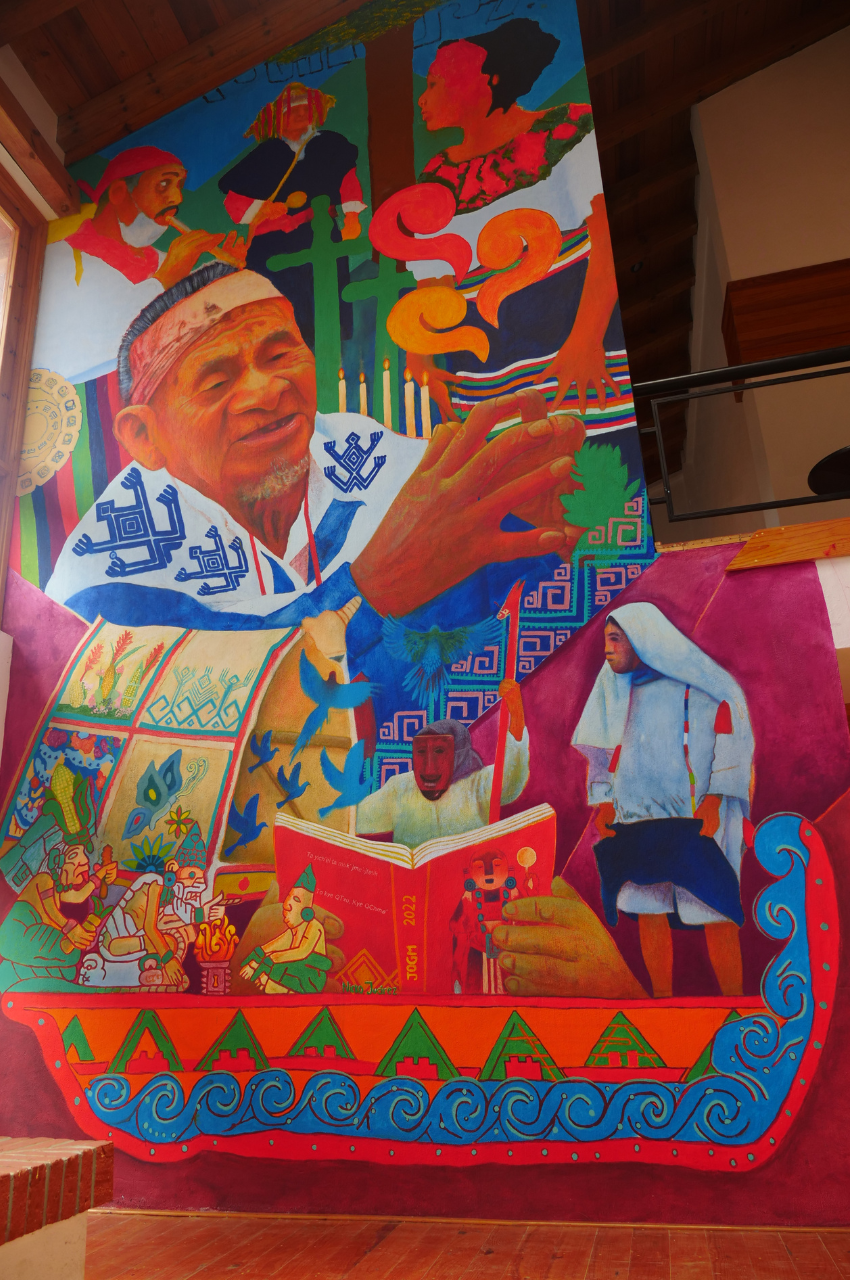

They know that I'm a Native woman and they call me their Niimiipuu sister. How did your trip to Chiapas come about? I am a member of Luk’upsíimey: the North Star Collective, which was formed in August 2020. We are a group of Nez Perce artists, scholars, creative writers, and Indigenous language activists who write and perform in Niimiipuutimtki. As a member of this group, I proposed a Nez Perce delegation to Chiapas. Our delegation was comprised of four Luk’upsíimey members, plus two professors to help with translations. We did extensive photo documentation and recorded videos of events that we did together with Mayan writers.

Lu’kupsíimey member Kellen Lewis, translator Silvia Soto, Lu’kupsíimey members Phil Cash Cash, Julian Ankney, and Inés Hernández-Ávila at CELALI in Chiapas, Mexico. (Photo courtesy: Inés Hernández-Ávila)

Was there a specific moment that inspired you during the trip?

One important experience that we couldn't record was when we visited one of the Zapatista caracoles, or centers. We had a great conversation with the Junta del Buen Gobierno (Council of Good Government), made up of three people taking their turn at being in charge of the community. Another experience which we couldn’t record was to visit the main ceremonial space of the Mayan people of San Juan Chamula, where they go on pilgrimage. A ceremony was performed to receive us on those lands. As Native people, we had to ask permission to be there and pay our respects, and they graciously received us. These are understandings that might not have been possible if we were not Native. Here, and throughout our visit, we made connections of the mind, heart and spirit, and now my Niimiipuu and Mayan colleagues know more about each other, and we can keep this exchange in our hearts for future work.

As Native people, we had to ask permission to be there and pay our respects, and they graciously received us. These are understandings that might not have been possible if we were not Native.

What role does public scholarship play in your research and teaching?

Public scholarship has to do with doing work that matters. For me, it has always involved engagement with Native/Indigenous communities and letting them know that I recognize my responsibility and accountability to them. I consider my first audience to be the people I am representing in my work. It's crucial to me that they are satisfied with how I've represented them. The Mayan peoples are the specialists of their own world, and if I can represent what they're doing in a way that dignifies them and shows that I understand what they're about, why they're doing what they're doing, and how they're doing it, then I feel that I'm a good, respectful scholar, collaborator and ally. When I started doing translation work, I translated the works of 20 writers from Chiapas, 18 Mayan poets and two Zoque poets (for a publication that is contracted to SUNY Press). It was challenging because the poets write in their original languages and Spanish, and I was working with the Spanish, which is already once removed from the original. So I had to work closely with each poet on every poem to make sure it was accurate. It's a process that requires close attention, and even some of the writers have pointed out the difficulty of translating their own works into Spanish from their original languages.

What this has highlighted is the significance of translation studies, and how the discipline of Native American and Indigenous Studies needs to consider this area as being pertinent to our field. It would be contrary to my awareness as an Indigenous human being to try to take credit for what I'm being gifted or what I'm learning from them and the communities I work with. That's why I won't ever say I'm a specialist in contemporary Mayan literature or that I discovered them. It's a different ethics, and ethics are really important to me, always in relation to representation. When we posture as discoverers, which I think academia encourages, the community itself can be objectified and not even seen as protagonists of their own destiny.

What question do you wish interviewers asked you (but they never do)?

"Why does it matter? Why do we have to look at hemispheric issues?” One of the challenges in the field of Native American and Indigenous studies, to me, is the inattention to the Spanish-speaking Americas (and Portuguese). Attention has mostly been on English-speaking nations that experienced principally British colonialism — the United States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. There is beginning to be more dedicated attention to Mexico, Central and South America, but I do note some continuing resistance to the South and the Spanish language. I think it's because of the circumstances of history and the distinct imperial/colonial projects. That’s beginning to change, but it’s not really where it should be.

Again, this is where translation projects become paramount. We need to know each other’s works. My project is only possible in our program because of our hemispheric approach, which is what has kept me at Davis all this time. Davis is really the only place where I can be myself and do what matters to me.

What is the importance of learning the languages of the people you work with?

In our graduate program, we always encourage students to learn the languages of the people they are working with, which in and of itself supports language revitalization. Not just exchanges like "How are you?" — what's most important is that Indigenous languages encode Indigenous belief systems. Learning an Indigenous language allows for a more profound investigation and a more accurate representation of peoples and communities. That was the other exciting part for us when we were in Chiapas — because we have an intuition that's being confirmed. In our discussions with our Mayan counterparts, we found that in our traditional teachings, we coincide.

For example, in our Niimiipuutimt culture, we believe that the heart leads, and that's the way the Mayan people are in Chiapas. They will ask you, "How is your heart today?" We also have what are called “original instructions” about how to be “true human beings,” and the Mayan understandings coincide with the Niimiipuu understandings. This is what I’m wanting to promote, that we are in sync with each other, we’re thinking similarly, and we have similar understandings, and yet we are distinct. I look forward to more such conversations, where we talk about not just Nez Perce or Mayans, but also Ojibwe, Yoeme, and other Native peoples whose belief systems insist that we be led by the heart, and who have similar concepts about being human. Rather than generalize, we need to meet and talk with each other, and when we’re ready, write about these exchanges and discoveries. Each people is unique, but when we share our belief-systems, we find we understand each other in revelatory ways.

Media Resources

More photos and information about this story are located on the Public Scholarship and Engagement web site