Why does memory fade? Why does it stay?

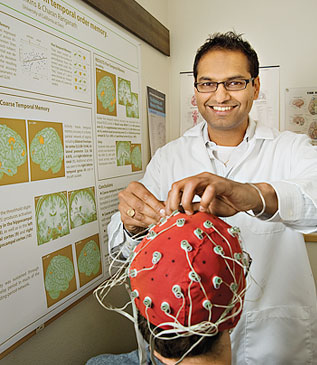

These questions, among others, occupy the mind of Charan Ranganath, a UC Davis psychology professor in the UC Davis College of Letters and Science and a core faculty member with the Center for Neuroscience. But the transient nature of memory isn’t just a focal point of Ranganath’s research. It’s something that he, like the rest of us, deals with daily.

“As a memory researcher, the most common question that I get in my everyday life is, ‘Why am I so forgetful?’” Ranganath said.

For Ranganath, forgetfulness often manifests as a misplaced pair of glasses or smartphone. But for others, memory lapses can be a sign of something more concerning.

Post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological conditions all affect memory. However, diagnoses of a condition like Alzheimer’s often come too late for effective intervention.

“By the time you reach this point, there’s already significant damage in the brain,” said Ranganath, who also directs the UC Davis Memory and Plasticity Program. “We need to detect people not at this point but rather at an earlier point, where people are just starting to deviate from the healthy trajectory of aging.”

In Ranganath’s lab, he and his colleagues are developing biomarkers to identify individuals with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. The hope is that early detection will allow for successful intervention.

Why do we forget?

The brain is a marvel of evolution. Yet even the healthy brain, according to Ranganath, isn’t designed to remember everything. A host of factors contribute to this daily forgetfulness.

“The biggest culprit in probably our everyday life is multitasking,” Ranganath said. “We don’t remember things often because we were never there in the first place. We’re checking our phones, being distracted by noises on the street and so forth, and all these things really degrade our capability to remember.”

Stress, fatigue and lack of sleep are also contributors to forgetfulness.

“When we’re under stress, we often have trouble forming new memories,” Ranganath said. “And as we get older, we definitely get less sleep and that leads to fatigue during the daytime, but also impairs our ability to solidify our memories during the night when we normally sleep.”

Why do we remember?

For Ranganath, a more pertinent question than “Why do we forget?” is “Why do we remember?”

It turns out that memory serves different purposes throughout a human lifespan. For adults, memory is often used to achieve goals or to assist with familial/communal activities. For children, it’s harnessed to build a sense of self, to explore the world and to learn. And in older adults, memory assists with cultural transmission — the passing of knowledge to the next generation.

Though memory plays different roles during a person’s life, there are steps one can take to promote healthy brain aging.

In a recent study, published by the British Medical Journal and referenced by Ranganath, researchers tracked roughly 29,000 participants over 10 years and discovered that a healthy lifestyle was associated with a slower memory decline. The six healthy lifestyle factors measured in the study included a healthy diet, regular physical exercise, active social contact, active cognitive activity, never or previously smoked and never drinking alcohol.

“The people with the most favorable lifestyle maintained more of their memory functions over this 10-year period than people who maintained an unfavorable lifestyle,” Ranganath said. “It’s quite a significant and meaningful difference.”

Detecting hidden signs of Alzheimer’s

While maintaining a healthy lifestyle promotes healthy brain aging, it’s not a panacea. As Ranganath said, “All of us know somebody who could’ve lived a very healthy lifestyle and still, nonetheless, succumbed to neurodegenerative disease.”

That’s why Ranganath and his team are developing biomarkers to detect preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. They’ve focused their sights on an area of the brain called the lateral entorhinal cortex (LEC).

“The LEC is important because it’s ground zero for damage in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease,” Ranganath said. “This is the stage we can’t identify in typical adults.”

The type of LEC damage characteristic of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease isn’t easily ascertained in living patients. Oftentimes, to glimpse such damage, a researcher needs to view a slice of a brain sample under a microscope. Ranganath and his team are figuring out how to assess this pathology in a noninvasive way.

“The brain is an interconnected network and even if only one area is showing pathology, like the LEC, we can see how it can affect memory in a broader way,” Ranganath said. “By doing this, we can understand how subtle dysfunction in the LEC can cause age-related and pathological changes in memory that we can measure in larger areas of the brain, like the hippocampus.”

“Through basic and translational neuroscience partnerships, we’re hoping to be able to build new treatments for detection and intervention of Alzheimer’s disease,” he added.

Media Resources

Greg Watry is a science writer in the UC Davis College of Letters and Science. This article was originally published on the college's website.