It’s the turn of the 19th century and botany is the only socially acceptable science for women to pursue. After all, both women and plants are “delicate,” so naturally botany is “fashionable.”

At least, that was society’s thinking at the time.

Women took this opportunity to shape the field of botany within a highly whitewashed and male-dominated world of science. Still, even if they had the same professional training as male botanists, women were labeled as “amateurs” or “connoisseurs,” and their history was largely erased.

Marina LaForgia, UC Davis postdoctoral scholar, winner of the prestigious 2022 L’Oréal For Women in Science Fellowship, and recipient of the Chancellor's Award for Excellence in Mentoring Undergraduate Research, sheds light on these inspiring women through her first year seminar, “Badass Babes of Botany.”

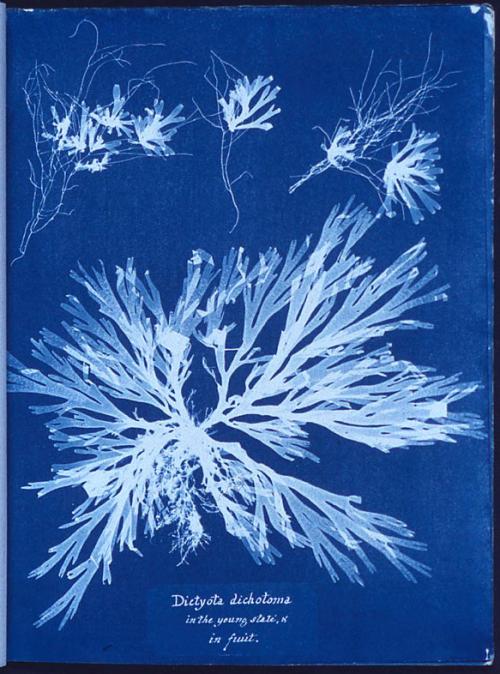

The women LaForgia highlights fought back in pursuit of knowledge. Jeanne Barrett (1740-1807) disguised herself as a man and conducted botanical surveys, becoming the first woman to circumnavigate the globe. Anna Atkins (1799-1871) was the first person to publish a book with photographs––cyanotypes of the algae she studied.

Women botanists were among the first women to graduate college and become scientists.

UC Davis Professor Katherine Esau was the first botanist to receive the National Medal of Science and was one of the most influential plant biologists in history before she died in 1997 at age 99. She broke barriers for women in science, and her name now graces the Katherine Esau Science Hall on campus.

“[Women] are trained to be homemakers. And I was not a homemaker,” said Esau.

But not all women scientists get recognized in this way. Not even LaForgia knew these botanists before starting her class.

After finding out about Anna Atkin’s cyanotypes, she started digging: “I didn’t know she existed. I was like, who else do I not know exists?”

Who are the Fab 5?

Women botanists ruled the field. For LaForgia’s week on taxonomy, she designated her “Fab 5:" Kate Brandegee, Alice Eastwood, Ynes Mexia, Blanche Trask, and Lester Rowntree. These women were instrumental in documenting and understanding California plant species in the early 1900s, and their collaboration resulted in much of what we know today about the plants in and around California, said LaForgia.

“These women are the epitome of badass: They fought against the stereotypes of their times, were among the first women to earn advanced degrees, and traveled to remote places in search of new and rare plant specimens,” LaForgia wrote in her description of the seminar.

Badass indeed: When the California Academy of Sciences caught fire in 1906, Alice Eastwood entered the burning building and saved 1,500 key reference (type) specimens. For the next 40 years, she rebuilt the collection to three times the amount destroyed in the fire.

Eastwood traveled around California in an open-top Model T Ford with Ynes Mexia, whose 13-year career began in her 50s. During that short time, Mexia traveled the world and collected nearly 150,000 specimens, described 500 new species, discovered two new genera, and had 50 plants named in her honor.

Kate Brandegee spent her honeymoon walking from San Diego to San Francisco, collecting plants along the way. She was the third woman to graduate from UC Berkeley, and she made it possible for West Coast botanists to publish their findings by founding the bulletin of the California Academy of Sciences. Brandegee took a pay cut to pay Eastwood as her assistant after seeing Eastwood’s huge personal collection of botanical specimens. Self-taught Eastwood took over at the Cal Academy when Brandegee retired.

Blanche Trask spent her career on Catalina Island documenting plants and writing poetry: “I have never known anyone anywhere who knows the plants individually over such a large area as she does” said botanist Willis Linn Jepson. “She seems to know the individual trees and shrubs like old friends and knows whether they have changed in the last 10 years and how much.”

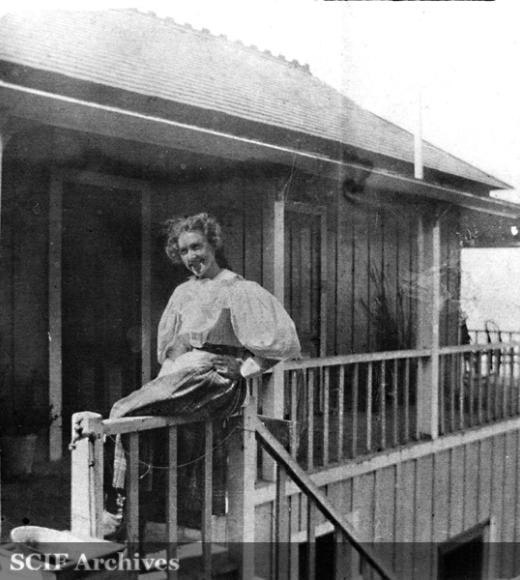

The last of the Fab 5, Lester Rowntree, began her career in botany in her 50s after her divorce and went on to found the California Horticultural Society with Eastwood. Rowntree traveled California alone in her car, and when her car couldn’t go any higher in the mountains, she’d go via mule. She’s the O.G. vanlife granola girl, a pioneer in California native plant propagation and conservation, and the founder of her own seed company.

“It took adversity to bring me the sort of life I had always longed for,” Rowntree wrote in her 1936 book, Hardy Californians.

(This girl group rivals any I’ve seen. I can just imagine the BuzzFeed quiz, “Which Member Of The Fab 5 Of Botany Are You?")

Inspiring young botanists

In her undergrad and high school years, LaForgia was deterred from her passion for science.

“I didn’t see people who looked like me,” she said. “To me, a scientist was an old white man in a lab coat. And it’s just so much more than that. It has been more than that for a long time. I wish someone would have just shaken me and been like, ‘Whatever. You’re worth it. Just do it.'"

She hopes to be that person for her students now.

“It’s inspiring to see other women,” said first-year Plant Sciences major B’Elanna Pho, who started volunteering at the UC Davis Herbarium after LaForgia took the class there.

“I originally wanted to go into geology, but one of the botanist highlights of the week was actually a paleobotanist, so now I want to do that,” said first-year student Keira Baum. “There are all of these women I’ve never heard of before, and they pioneered this entire field. They wanted to study science and they did, even though science wasn’t reserved for them. It’s fascinating.”

Even if the students aren’t in her field, LaForgia hopes they walk away from her class with confidence, and the knowledge that the history she is sharing applies to any career.

“There are amazing women and people of color and minorities that are also in those fields,” said LaForgia. “I also hope the students get more excited about plant life and nature in general. We need more people conserving and protecting nature, ensuring that there are these beautiful areas in the future.”

Malia Reiss is a science news intern with UC Davis Strategic Communications. She studies environmental science and management at UC Davis.

Media Resources

Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu