The number of mule deer, coyote and other wildlife getting hit by vehicles on California’s roadways is falling, signaling a decline in some key animal populations in the state, according to an annual report from the Road Ecology Center at University of California, Davis.

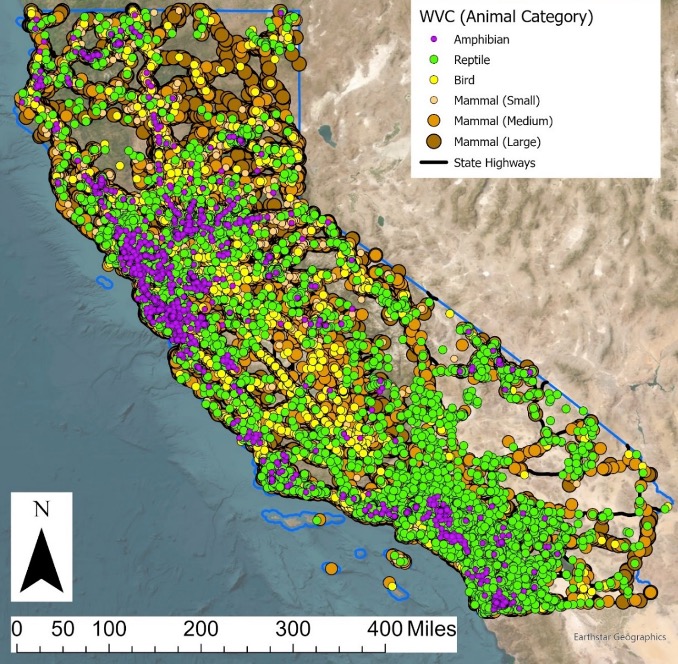

The annual report, which analyzes roadkill observations on local roads and state highways across the state, identifies more than 600 collision hot spots and emphasizes the need for fencing to protect animal and human lives.

“Traffic impacts are a massive problem in California and throughout the world,” said Fraser Shilling, director of the UC Davis Road Ecology Center. “Adequate roadside fencing would reduce wildlife being hit by vehicles.”

The hot spots include:

- Bay Area: I-680, I-280, SR 17

- Sacramento/Placerville: SR 49, I-80, U.S. 50

- Central Sierra Nevada: SR 108, SR 88, SR 4

- Central Coast and Southern: I-405, U.S. 101, SR 154

Evidence-based decisions needed

The report also applauds the state for approving nearly $1 billion in funding to build wildlife crossings, fencing and other mitigation, but says site selection for current and future projects could be better informed by wildlife data.

It highlights a $135 million state plan to prevent collisions by building wildlife crossings across Interstate 15 along a proposed train route that a privately owned company is planning to build between Los Angeles and Las Vegas. The area is not a hot spot for collisions in the region.

The report presses for improved, evidence-based, decision-making about the need for roadside wildlife fencing and where to place and design crossing structures for wildlife connectivity.

Declines may not be good news

At first glance, a decline in roadkill cases may seem positive, but rates of roadkill can be an indicator of trends in wildlife population changes, particularly if animal movement and traffic patterns did not change.

In the case of mule deer, the reduction in collisions indicate a roughly 10% population decline every year for seven years. For coyotes, the decline was by 5% per year in the same time period, Shilling said.

“For many species the relationship between collisions and population is pretty strong,” he said. “This is a fairly drastic decline.”

Over nearly 15 years, the Road Ecology Center has amassed a database of more than 200,000 crash and roadkill incidents reported by state agencies, law enforcement, wildlife groups and scientists, as well as members of the public via the California Roadkill Observation System. That detailed collision information allows Shilling and others to pinpoint hot spots, work to improve habitat connectivity and see other trends.

“California’s roads witness a higher toll of wildlife-vehicle collisions than people may imagine,” said Mari Galloway, California programs director for the nonprofit Wildlands Network. “This data provides crucial insights on where we can best reduce this mortality, emphasizing the need to prioritize safety and conservation efforts to protect our wildlife.”

Increasing collisions for some

Mountain lions and black bears are highly vulnerable to vehicle strikes as they traverse large range areas, and that movement increases in times of drought as they forage for food. Collisions for those two species have increased by 10% between 2016 and 2022, the report finds.

The report supports observations by mountain lion experts that vehicle collisions are likely the first or second leading cause of death for mountain lions in Southern California. The resultant smaller and segmented populations can reduce genetic diversity and lead to inbreeding, said T. Winston Vickers, an associate veterinarian with the UC Davis Karen C. Drayer Wildlife Health Center, who contributed to the report.

“This report once again emphasizes how much preventable mortality of wildlife occurs on California roads and the impact not only on the animals but on humans, as well,” Vickers said. “These road effects lead to inbreeding and smaller populations overall — the net effect being that entire mountain lion populations are threatened with local extinction.”

Vehicle strikes in California add up to an estimated $250 million annually in driver injury and death, vehicle damage, lost wildlife values, emergency response, time away from work and other costs. But they can be reduced. Adding 1 mile of fencing along 669 specific highway miles would have saved $200,000 per mile between 2016 and 2022, according to the report.

“There’s a lot of costs that go into each crash,” Shilling said. “Fixing the problem with adequate fencing tends to pay for itself in terms of reduced crashes.”

A crossing for bighorn sheep

This year the Road Ecology Center received a $5.8 million grant from the California Wildlife Conservation Board to plan a wildlife crossing for the endangered Peninsular bighorn sheep in Imperial County along Interstate 8. Shilling and center staff will work with tribal groups and others as they select a site location, design the project and address environmental issues to present a shovel-ready construction project.

The project will include fencing, which stops animals from entering roadways, and a crossing that allows movement over the roadway.

The report urges the state to spend its transportation funds to reduce collisions and associated costs, which would benefit public safety while reducing wildlife deaths.

“While the findings are distressing, they can serve as a roadmap to improve our roadways and build more effective wildlife crossings and appropriate fencing,” said Tiffany Yap, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity. “Saving the lives of bears, mountain lions and deer also means making highways safer for people, too.”

Road Ecology Center analyst David Waetjen and student interns Christina Cruz Andrade, Madison Burnam, Phoebe Lau, Julianne Mackey, Michelle See, Claire Short and Natalia Younan contributed to the report.

Media Resources

Media Contacts:

- Fraser Shilling, UC Davis Road Ecology Center, fmshilling@ucdavis.edu

- Emily C. Dooley, UC Davis News and Media Relations, ecdooley@ucdavis.edu

- Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu

Additional photos for download with credit to UC Davis Road Ecology Center.