Quick Summary

- Researchers infer that women can buffer themselves against economic and social crises, and more effectively keep their children alive

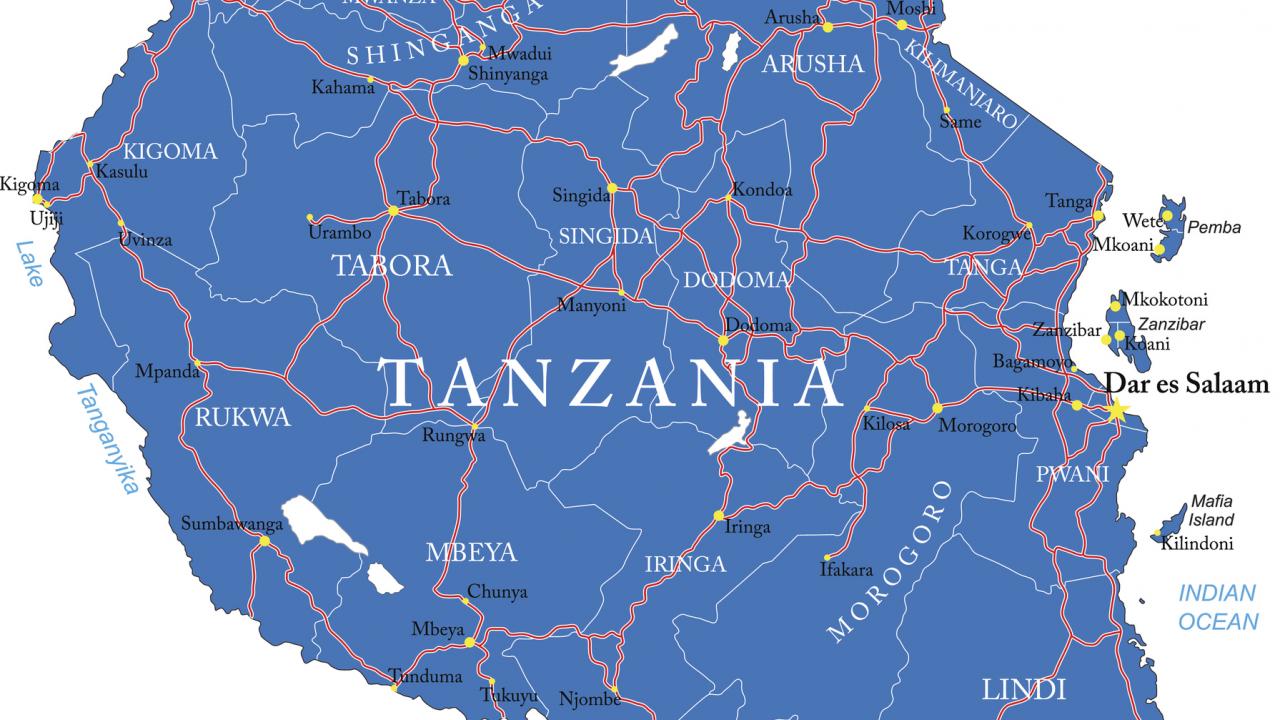

- Researchers collected data on nearly 2,000 individuals living in a small village at the north end of the Rukwa Valley, Tanzania

It is well known that men benefit reproductively from having multiple spouses, but the reasons why women might benefit from multiple marriages are not as clear. Women, as a result of pregnancy and lactation, can’t reproduce as fast as males.

But new research by the University of California, Davis, challenges evolutionary-derived sexual stereotypes about men and women, finding that multiple spouses can be good for women too.

“We can’t pin down the exact reasons for this finding, but our work (together with suggestions of others) suggests that marrying multiply may be a wise strategy for women where the necessities of life are hard, and where men’s economic productivity and health can vary radically over their lifetime due to the challenging environmental conditions,” said the lead researcher, Monique Borgerhoff Mulder, UC Davis professor of anthropology.

Women can buffer themselves against effects of the economy

Researchers infer that by acquiring multiple spouses, women can buffer themselves against economic and social crises, and more effectively keep their children alive.

Borgerhoff Mulder collected data on births, deaths, marriages and divorces of all households in a western Tanzanian village over two decades. A longitudinal study like this is “much more reliable than records collected retrospectively,” said the study’s co-author, Cody Ross, currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig.

Working with the demographic data, Ross found that women who moved from spouse to spouse tended to have more surviving children, controlling for the number of years they had been married. Men by contrast, again controlling for their number of married years, tended to produce fewer surviving children with the individual women they married over their lives.

Researchers collected data on nearly 2,000 individuals living in a small village at the north end of the Rukwa Valley, in an area adjacent to floodplains and woodlands now designated as Katavi National Park. The people who live there are of Pimbwe and related Bantu ethnicity. The Pimbwe people have a long history of hunting, fishing, and farming cassava and maize. They also gather honey, brew beer and conduct small business. But crop yields are unreliable owing to unpredictable rainfall, poor soil conditions, agricultural pests and theft.

The latest paper, published Aug. 14 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, represents a culmination of two decades of work by Borgerhoff Mulder, who has written extensively about the lives of men and women in this small village in western Tanzania where she conducts anthropological and demographic research.

“As evolutionary biologists we measure benefit in terms of numbers of surviving children produced — still a key currency in rural Africa,” explained Borgerhoff Mulder. “… it bears emphasizing that in many parts of rural Africa reproductive inequality among women emerges not from reproductive suppression as in some other highly social mammals … but more likely from direct competition among women for access to resources.” These resources include high-quality spouses, multiple caretakers to help around the house and farm, and (at least in this particular cultural context) helpful in-laws, she said.

Marriage in the Pimbwe culture is informal — defined as sexual partners living together. Accordingly, “divorce is easy, and can be initiated by either partner,” as both Borgerhoff Mulder and early 20th century missionary visitors to the area have observed. Both men and women may have more sexual partners than marriage partners, but sexual partnerships are quickly recognized as marriages, researchers said.

Media Resources

Karen Nikos-Rose, News and Media Relations, 530-219-5472, kmnikos@ucdavis.edu