The Earth formed relatively quickly from the cloud of dust and gas around the sun, trapping water and gases in the planet’s mantle, according to research published Dec. 5 in the journal Nature. Apart from settling Earth’s origins, the work could help in identifying extrasolar systems that could support habitable planets.

Drawing on data from the depths of the Earth to deep space, University of California, Davis, Professor Sujoy Mukhopadhyay and postdoctoral researcher Curtis Williams used neon isotopes to show how the planet formed.

“We’re trying to understand where and how the neon in Earth’s mantle was acquired, which tells us how fast the planet formed and in what conditions,” Williams said.

Neon is actually a stand-in for where gases such as water, carbon dioxide and nitrogen came from, Williams said. Unlike these compounds that are essential for life, neon is an inert noble gas, and it isn’t influenced by chemical and biological processes.

“So neon keeps a memory of where it came from even after four and a half billion years,” Mukhopadhyay said.

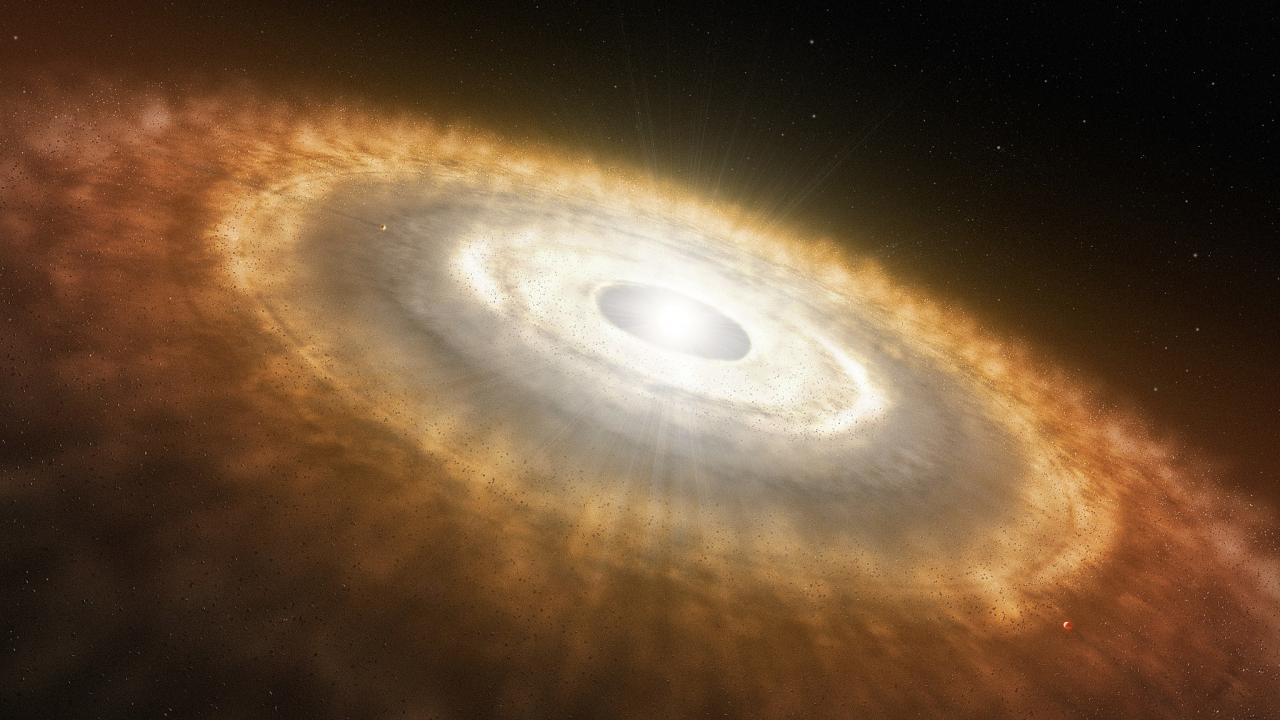

There are three competing ideas about how the Earth formed from a protoplanetary disk of dust and gas over 4 billion years ago and how water and other gases were delivered to the growing Earth. In the first, the planet grew relatively quickly over 2 to 5 million years and captured gas from the nebula, the swirling cloud of dust and gas surrounding the young sun. The second theory suggests dust particles formed and were irradiated by the sun for some time before condensing into miniature objects called planetesimals that were subsequently delivered to the growing planet. In the third option, the Earth formed relatively slowly, and gases were delivered by carbonaceous chondrite meteorites that are rich in water, carbon and nitrogen.

These different models have consequences for what the early Earth was like, Mukhopadhyay said. If the Earth formed quickly out of the solar nebula, it would have had a lot of hydrogen gas at or near the surface. But if the Earth formed from carbonaceous chondrites, its hydrogen would have come in the more oxidized form, water.

Neon from ocean floor to deep space

To figure out which of the three competing ideas on planet formation and delivery of gases was correct, Williams and Mukhopadhyay accurately measured the ratios of neon isotopes that were trapped in the Earth’s mantle when the planet formed. Neon has three isotopes, neon-20, 21 and 22. All three are stable and nonradioactive, but neon-21 is formed by radioactive decay of uranium. So the amounts of neon-20 and 22 in the Earth have been stable since the planet formed and will remain so forever, but neon-21 slowly accumulates over time. The three scenarios for Earth’s formation are predicted to have different ratios of neon-20 to neon-22.

The closest they could get to the mantle was to look at rocks called pillow basalts on the ocean floor. These glassy rocks are the remains of flows from deep in the Earth that spilled out and cooled in the ocean, later to be collected by a drilling expedition led by the University of Rhode Island, which makes its collection available to other scientists.

The gases are found in tiny bubbles within the basalt. Using a press, Williams cracked basalt chips in a sealed chamber, allowing the gases to flow into a sensitive mass spectrometer.

Now for the space part. Previous researchers established the neon isotope ratio for the “solar nebula” (early rapid formation) model with data from the Genesis mission, which captured particles of the solar wind. Data for the “irradiated particles” model came from analyses of lunar soils and of meteorites. Finally, carbonaceous chondrite meteorites provided data for the “late accretion” model.

Minimum size for a habitable planet

The isotope ratios they found were well above those for the “irradiated particles” or “late accretion” models, Williams said, and support rapid early formation.

“This is a clear indication that there is nebular neon in the deep mantle,” Williams said.

Neon, remember, is a marker for those other volatile compounds. Hydrogen, water, carbon dioxide and nitrogen would have been condensing into the Earth at the same time — all ingredients that, as far as we know, go into making up a habitable planet.

The results imply that to absorb these vital compounds, a planet must reach a certain size — the size of Mars or a little larger — before the solar nebula dissipates. Observations of other solar systems show that this takes about 2 to 3 million years, Williams said.

Does the same process happen around other stars? Observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter Array, or ALMA, observatory in Chile suggest that it does, the researchers said.

ALMA uses an array of 66 radiotelescopes working as a single instrument to image dust and gas in the universe. It can see the planet-forming disks of dust and gas around some nearby stars. In some cases, there are dark bands in those disks where dust has been depleted.

“There are a couple of ways dust could be depleted from the disk, and one of them is that they are forming planets,” Williams said.

“We can observe planet formation in a gas disk in other solar systems, and there is a similar record of our own solar system preserved in Earth’s interior,” Mukhopadhyay said. “This might be a common way for planets to form elsewhere.”

The work was funded by the National Science Foundation.

Media Resources

Sujoy Mukhopadhyay, Earth and Planetary Sciences, smuk@ucdavis.edu

Curtis Williams, Earth and Planetary Sciences, cdwill@ucdavis.edu

Andy Fell, News and Media Relations, 530-752-4533, ahfell@ucdavis.edu