From the earliest moments of his childhood, Gary May was building. He recalls spending countless hours assembling structures with Lego bricks and Erector sets and creating imaginary worlds and characters inspired by the comic books he loved reading and collecting.

May credits his parents for nurturing his creativity and encouraging self-confidence. They dedicated time for homework every school night and often gave him $1 — “enough for six comic books back then” — for every “A” he received in class. All the while, his parents instilled their firm belief in the transformative power of education. As May said, his parents “always wanted the best for me in life and knew that an education would help me reach whatever goals I set.”

AMONG THE ACADEMIES

UC Davis has more than 50 faculty members who belong to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, a recognition of their distinguished and continuing achievements in research. The academies are among the most prestigious membership organizations in the world.

Each month, Dateline UC Davis will profile one of these faculty members in honor of their contributions to scientific research and knowledge.

Those twin commitments — to education and building a better world — have characterized May’s career, from high school through his work as an electrical engineer and college dean to his role as the chancellor of UC Davis.

As he marks seven years in that role this month, May notes he took the position of chancellor after 26 years at Georgia Tech because he wanted to “come to a high-quality institution on the rise, one where I could move the needle, advancing the university forward.”

As May sees Aggie Square rising over the Sacramento skyline, outside research funding for the university crossing the $1 billion threshold in both 2021-22 and 2022-23, and the university climbing to No. 6 among public universities in the US News & World Report rankings, he remains optimistic about UC Davis’ future. Whether it’s enhancing global food security, protecting the environment or advancing animal and human health, he says the university “has so much potential in areas that will be important to not just California and the nation, but the world.”

Pioneering work and achievements

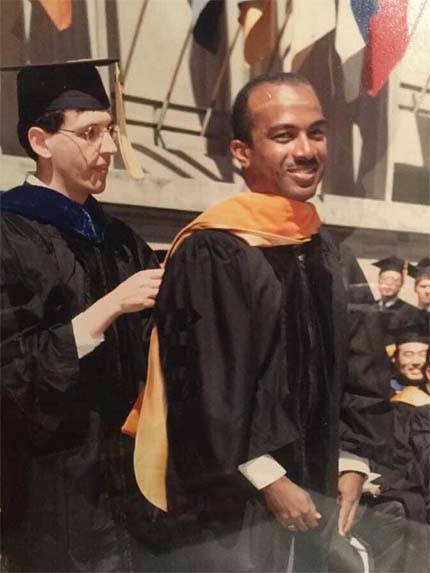

He’s earned many accolades along the way, including recognition from prestigious organizations. May was named to the National Academy of Engineering in 2018 for contributions to semiconductor manufacturing research and innovations in educational programs for underrepresented groups in engineering. In 2020, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences for educational and academic leadership.

As a student and electrical engineer, May researched the semiconductors that power almost every modern electronic device, from our phones to our cars. May’s work focused on “determining ways to model and control and make more efficient the processes that go into manufacturing these integrated circuits for major manufacturers like Texas Instruments, Intel and Samsung.”

The draw and the challenge of the work that powered these semiconductors fabrication plants, May said, was that “you can’t make mistakes, and you can’t have inefficiencies.”

May was also an early pioneer in artificial intelligence through his work to improve the semiconductor manufacturing process. In the early 1990s, May and his team at Georgia Tech were among the first to use “neural networks, which are now called deep learning models, to model manufacturing processes more efficiently than the statistical models of the time.”

May notes that this work increased efficiency in semiconductor manufacturing because “computers of the time weren’t up to” the task of the demanding calculations necessary to model the manufacturing process.

May remains optimistic about the future of artificial intelligence but believes we must “be intentional about making sure there’s a level of equity in how AI models are developed” moving forward.

A critical turning point in May’s journey to electrical engineering came as a high school student, when he was invited to the Develop Engineering Students program in St. Louis, his hometown. The program connected local business and industry leaders with minority students with high potential, teaching them the work of engineers on job sites and in classrooms.

For three summers, May built academic skills like math and practical skills like soldering — which he would need as an engineer. He credits the program with preparing him for the rigor of the engineering program at Georgia Tech.

Lifting others up

May never forgot the importance of mentoring, something that became a throughline of his career.

Inspired by mentors like Professor Augustine O. Esogbue, who encouraged him as an engineering student, and Georgia Tech President Wayne Clough, who encouraged him to become an education leader, May knew he had an obligation to pay that support forward.

Because of their guidance and his experience as one of just a handful of people of color pursuing an advanced degree in engineering, May committed himself to mentoring and building programs for other students of color to feel welcome and encouraged on their path.

At Georgia Tech, May started the Summer Undergraduate Research in Engineering/Science, or SURE, program, designed to attract qualified underrepresented minority and women students to graduate school in engineering and science.

He says he is proudest of founding the Facilitating Academic Careers in Engineering and Science program, which encourages minority engagement in engineering and science careers in academia. During May's 10-year involvement in the program, 430 students of color — more than anywhere else in the country — received their doctoral degrees in science, technology, engineering or math fields.

The SURE program is still operating today.

At a recent event in St. Louis honoring high school winners of National Society of Black Engineers scholarships, May was thanked and introduced by Saint Louis University School of Science and Engineering Dean Gregory Triplett, whom May had mentored as a doctoral student.

May considers mentoring one of his most important roles and said he still “gets a big charge out of seeing somebody I've mentored have success.”

May cites the term's origin to explain his belief that mentoring must mean more than occasional meetings over lunch.

“When Odysseus left his home, he left his son in the care of Mentor for his care and safekeeping,” May said. “If you're a mentor, you really are deeply engaged with your mentee, you have common ground, and you try to build ongoing relationships.”

Future goals

Looking ahead, May wants to continue to spread the word about how UC Davis is building a better world, both through innovations like the dozens of strawberry varieties produced by the Strawberry Breeding Program over the decades to work like that of the Immigration Law Clinic, which represents detained immigrants before the immigration court and was the first of its kind in the nation.

“I’m constantly surprised by the exceptional discoveries here,” he said. “We’re doing amazing things. I’m optimistic that so much good can come from this place.”

Media Resources

D Allan Pogreba is a speechwriter in the Office of Strategic Communications, and can be reached by email.