Quick Summary

- Campus school reopens safely with reduced enrollment

- Children find care and connection, and new ways to learn

- Enriched experience will live on in early childhood education

Teacher Patty Yeung kneels down with a container of ladybugs, and six tiny children encircle her like a hug. She gently lifts the lid, releasing a cloud of ladybugs into the spring garden at the Early Childhood Lab School.

THE SCHOOL

The Early Childhood Lab School is operated by the Center for Child and Family Studies, Department of Human Ecology, in the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences.

•••

Photos and video by Hector Amezcua/College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences

“Open your palm and let them come to you,” Yeung says as the ladybugs flit amid the lavender and fava beans and the toddlers’ outstretched arms.

A year ago, this preschool yard was vacant, closed down along with much of the UC Davis campus due to the spread of COVID-19. Last September, a small cohort of educators led by Kelly Twibell, director of the Early Childhood Lab School, found a way to safely open their doors to a few dozen children of essential workers in Davis and Sacramento. In the process, Twibell and her team have discovered ways to enrich childhood education now and into the future.

“The lockdown challenged us to reinvent what we do,” says Twibell, smiling as she watches the children play. “Working together, we’ve been able to create safe spaces where children can connect with their peers, build relationships with adults, and explore their world.”

Seeing beyond the masks

The Early Childhood Lab School is serving 24 children onsite and 30 remotely at the present time. That’s down significantly from the 84 children the school typically enrolls when some 50 undergraduates and student interns are onboard getting hands-on experience working directly with the kids.

The school follows strict COVID-19 protocols, including frequent hand-washing and mandatory mask-wearing, which makes for an interesting challenge when teaching toddlers how to recognize emotions.

“We usually talk a lot about reading faces to understand how people are feeling,” Twibell explains. “Now with masks, we encourage children to listen and look at each other more closely to pick up clues.”

What can you tell by the sound of someone’s voice? Why are your friends’ shoulders slumped? Did you notice that their eyebrows are raised?

“Masks allow us to explore a deeper layer of understanding,” Twibell says. “We find ourselves paying closer attention to those around us, which is valuable for all of us as we navigate a post-pandemic world.”

Hands-on remote learning

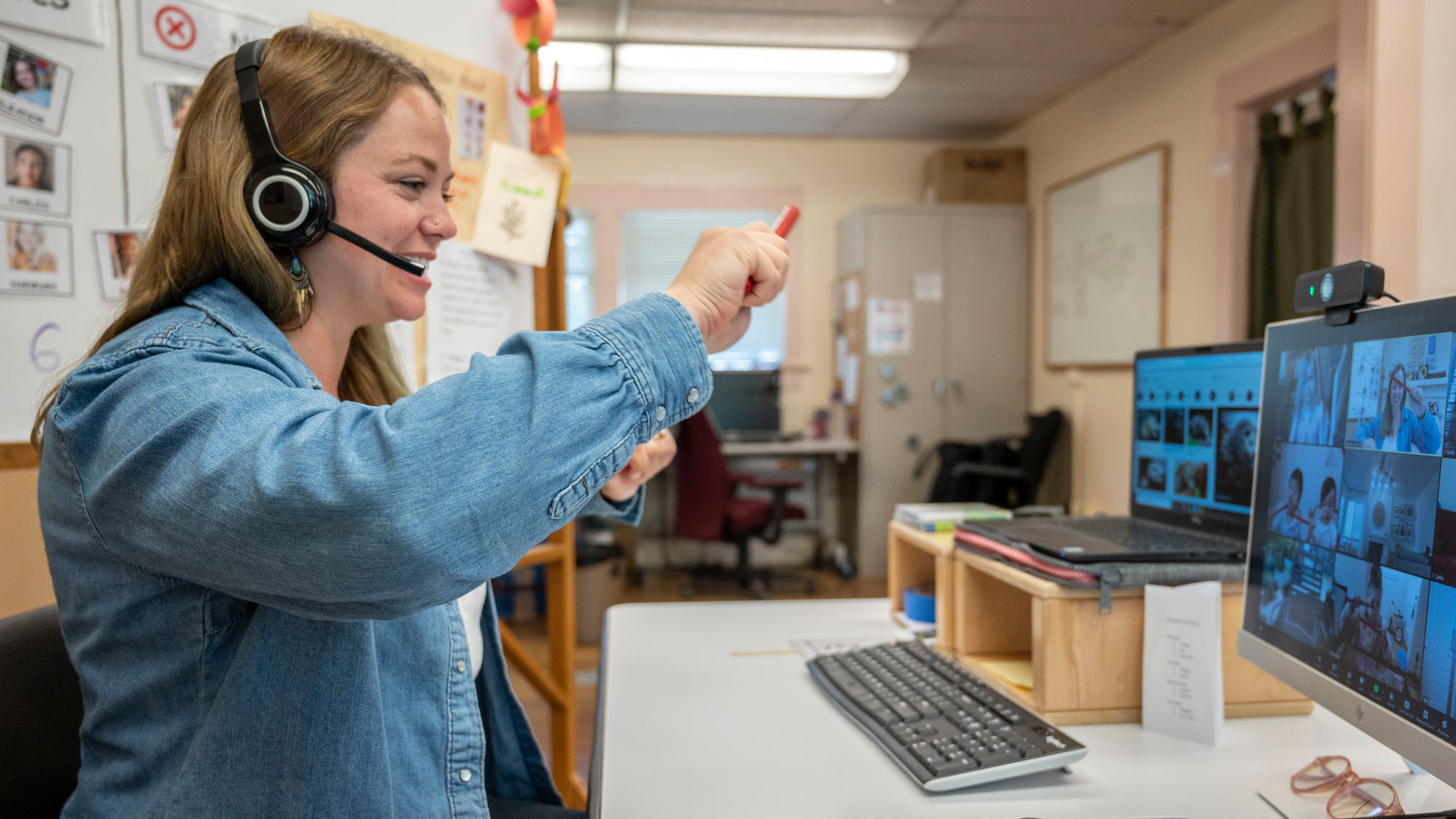

“Wave your scarf up and down, up and down, up and down.” Lecturer Hannah Minter Anderson sings and waves a scarf while a screen full of attentive toddlers sing and wave scarves (and a random sock) along with her.

“That’s right! You got it!” Anderson beams.

When you walk into Anderson’s remote-learning classroom, you might feel like you’re on set of the Mister Rogers Neighborhood television show. There’s the class pet (a stuffed squirrel named Frederico), a wall of colorful artwork and a teacher with a warm, welcoming smile.

The difference is, the children in this online experience are not viewers. They are active participants, stacking blocks or planting seeds or playing rhythm sticks along with Anderson and one another. When one child shares a toy dinosaur with the group, the other children scramble off screen and bring back toys of their own to show and tell.

“The children end up having conversations with each other, not just with me,” Anderson says. “They send cards to each other and invite each other to their virtual birthday parties. They’re building lasting friendships, even though they haven’t yet met in person.”

Activity kits are keepers

Each week, Anderson curates a kit of materials and activities — like paints, seeds and blocks — that parents bring home so children can play and learn along together with their online classmates. Some weeks they become astronauts, some weeks they pretend to be rock stars, some weeks they are architects building towers to the sky.

“The kits are so successful that we want to build on them even after we return to fully staffed in-person classrooms,” Twibell says. “This type of hands-on remote learning could expand the reach of childhood education into areas where families don’t have many options for high-quality care. These activity kits can give parents and providers the resources they need.”

Keeping connections alive

Outside, the children continue their adventures. Some toddlers gather roly-poly bugs to place in habitats they built inside glass jars. Other children flap their arms like birds. One group stands at the perimeter of the schoolyard, weaving flowers into the fence to make it prettier for them and the outside world.

This fall, if all goes according to plan, UC Davis and this lab school could accommodate more in-person learning for preschool children and the undergraduates and student interns who work with them. Twibell welcomes the change and is happy to know that her team and community found a way to help children stay connected throughout the pandemic.

“Nature and children are so incredibly resilient,” she says. “The Earth keeps spinning, and we keep going. Sometimes, it’s the children who lead the way.”

Media Resources

Diane Nelson is a senior writer on the communications team in the College of Agricultural and Natural Resources. She can be reached by email or phone, 530-752-1969 (office) or 209-345-9496 (cell).