In research that incorporates food, sex and danger, scientists at the University of California, Davis, Bodega Marine Laboratory recently achieved the first successful captive spawning of the endangered white abalone in nearly a decade. The work may be the white abalone’s last chance at avoiding extinction.

White abalone have the bad luck of being both reportedly delicious and difficult to breed. Broadcast spawners, they reproduce by releasing their eggs and sperm into the water. Males and females must be in close proximity for sperm to find an egg. Prized by sport and commercial fisheries, the white abalone experienced a drastic population decline caused by overfishing. Currently, males and females are spread so far apart that they have little to no chance of reproducing successfully.

In 2001, the white abalone became the first marine invertebrate to be listed as an endangered species. Scientists now believe white abalone are no longer reproducing in the wild.

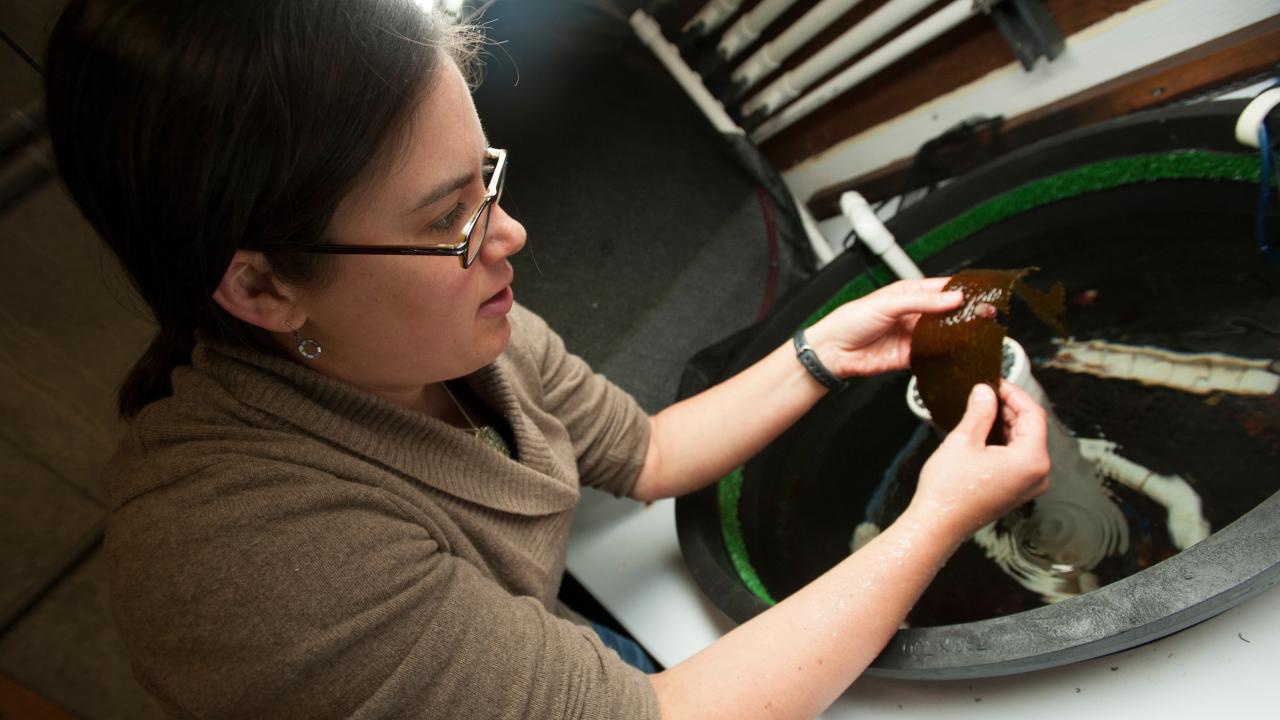

UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory is leading the science on a white abalone captive breeding program, which began in 2010. Researchers encourage the mollusks to breed in an advanced facility that allows scientists to use mood-setting enhancements, like optimum lighting and temperature controls, to cue the abalone to reproduce.

“We’re at a desperate time because all of the population models suggest that white abalone will be completely extinct within 10 to 15 years if we don’t have some sort of program like this for placing them back into the wild and trying to restore these populations,” said Gary Cherr, director of the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory and principal investigator of the captive breeding program.

A key challenge in breeding white abalone is that high mortality rates are part of their biology. While females can produce millions of eggs, only about 1 percent of them are expected to survive to become juveniles.

Between 2003 and 2012, no white abalone successfully spawned in captivity. However, in 2012, Bodega Marine Laboratory’s breeding program experienced the first successful spawning since 2003, and the lab repeated that success this past spring. There are currently about 60 adult abalone in captivity through the program now.

“UC Davis is the Match.com for white abalone,” said Kristin Aquilino, a postdoctoral scholar at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory. “There aren’t a lot of white abalone left in captivity, and we aren’t allowed to collect any from the wild. With the animals we’re producing now, we’re almost doubling the amount we have in captivity that we can spawn.”

The long-term goal is to build the population in captivity, outplant them to the wild and repopulate the Southern California subtidal zone with white abalone. Continued successful spawning results are considered vital to that effort.

"White abalone are simply disappearing in the wild," said Melissa Neuman, white abalone recovery coordinator at NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service. "The white abalone captive breeding program, like the one at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory, is quite likely the last hope to keep this species from blinking out of existence."

Partnering institutions in Southern California that are also holding white abalone include Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach, UC Santa Barbara, Cabrillo Marine Aquarium in San Pedro, and Ty Warner Sea Center in Santa Barbara.

The program is a collaboration among UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and California Department of Fish and Wildlife. The project receives funding from NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service.

Media Resources

Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu

Gary Cherr, Bodega Marine Laboratory, (707) 875-2051, gncherr@ucdavis.edu

Kristin Aquilino, UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory, 707-875-2045, kmaquilino@ucdavis.edu