Quick Summary

- People in unincorporated, rural, low-income communities have unsafe drinking water pouring from their taps

- Most people without safe water, or about 99,000 residents, live near public systems with clean water

- The study’s purpose is to inform state policy and local planning in order to improve access to safe drinking water for these communities

Tens of thousands of people living in the San Joaquin Valley’s unincorporated, rural, low-income communities have unsafe drinking water pouring from their taps. That water is delivered from a patchwork of community water systems that often don’t meet state or federal standards for drinking water, or from private wells that are not tested.

However, a University of California, Davis, study that assessed water systems throughout the valley found that safe water is often close at hand. Most people without safe water, or about 99,000 residents, live near public systems with clean water. They could access that water if service extensions, piping and other infrastructure were implemented, the report found.

“There are solutions,” said Jonathan London, associate professor, director of the UC Davis Center for Regional Change and lead author of the report.

HOW CLOSE?

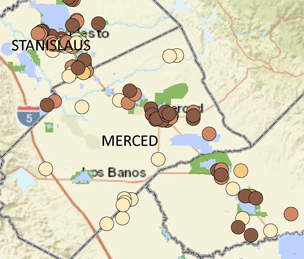

Click here to see the full map. Each dot represents a community without safe drinking water, and the dot's color indicates the distance from a source of safe water.

Some of that work is already happening. Students in the UC Davis School of Law Aoki Water Justice Clinic have been meeting with these communities to secure funding to build that infrastructure. Law students are also working with community organizations seeking policy changes to increase access to safe drinking water for low-income Californians.

“We are confident that these communities, local water systems, and the state can work together to fund and encourage infrastructure improvement to ensure that no one in the San Joaquin Valley need worry about what is coming out of their faucets,” London said.

The report, “The Struggle for Water Justice in the San Joaquin Valley: A Focus on Disadvantaged Unincorporated Communities,” looked at access to safe drinking water in low-income communities without city governments in the eight counties of the San Joaquin Valley.

The study’s purpose is to inform state policy and local planning in order to improve access to safe drinking water for these communities.

“Within the next decade and with adequate funding, we could solve a problem that has plagued low-income, rural communities for over 50 years,” said Camille Pannu, the water justice clinic director who also contributed to the report.

School of Law Water Justice Clinic

The Aoki Water Justice Clinic combines transactional law, policy advocacy and strategic research to ensure low-income California communities receive clean, safe and affordable drinking water. Established in 2017, it is believed to be the first law school clinic of its kind in the country.

- Law students in the clinic have worked in 13 low-income, rural communities in Fresno, Kern, Lake, Mono, Sonoma, Tulare and Tuolumne counties.

- Through their work, students have extended (or are in the process of extending) access to safe drinking water to 15,800 Californians.

- Four students are providing on-the-ground community organizations with policy research and analysis for state legislation introduced this year.

- Students are leading or supporting research collaborations, including partnerships with the UC Davis Center for Regional Change, UC Cooperative Extension and the UC Berkeley School of Law's Wheeler Water Institute.

Success stories are found already in Tulare and Kings counties

The report found that more communities need to follow the examples from Kings and Tulare counties, where residents with unsafe water recently consolidated some water delivery systems and added lines to provide safe drinking water to residents. Previously, the people in the affected communities had dangerous levels of arsenic and nitrates in their water supplies.

Using a combination of solutions, the communities forged agreements among existing water agencies and obtained grants to help finance the changes, and in some cases, the state ordered consolidations.

The poor and people of color are adversely affected

People of color made up a majority of those without safe water, the Center for Regional Change study found. For example, while Hispanics make up just under half, or 49 percent, of the total population of the San Joaquin Valley, they represent more than two-thirds of residents in these unincorporated communities and 57 percent of all residents served by out-of-compliance water systems. Caucasians account for about 36 percent of those receiving water from unsafe systems.

Those without safe water face additional economic burdens as they need to augment their water needs by buying bottled water, or purchasing filter systems, for drinking and cooking.

Study proposes practical solutions

Ways safe drinking water can be achieved, according to the report, include:

- Develop and strengthen consolidation and service extension mandates and incentives for cities, counties and community water systems.

- Create larger, more stable, and more equitably distributed and coordinated sources of funding for drinking water systems.

- Improve public access to data and planning tools; enhance existing data systems and coordinate water monitoring efforts.

The research began in fall 2016, and was funded by Resources Legacy Fund and the Water Foundation.

Media Resources

Karen Nikos-Rose, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-219-5472, kmnikos@ucdavis.edu

Jonathan London, Center for Regional Change, 530-219-9082, jklondon@ucdavis.edu