University of California, Davis, researchers have launched a new online database that can help community members, policymakers and advocates view and compare local governments’ vision for the future with the California General Plan Database Mapping Tool.

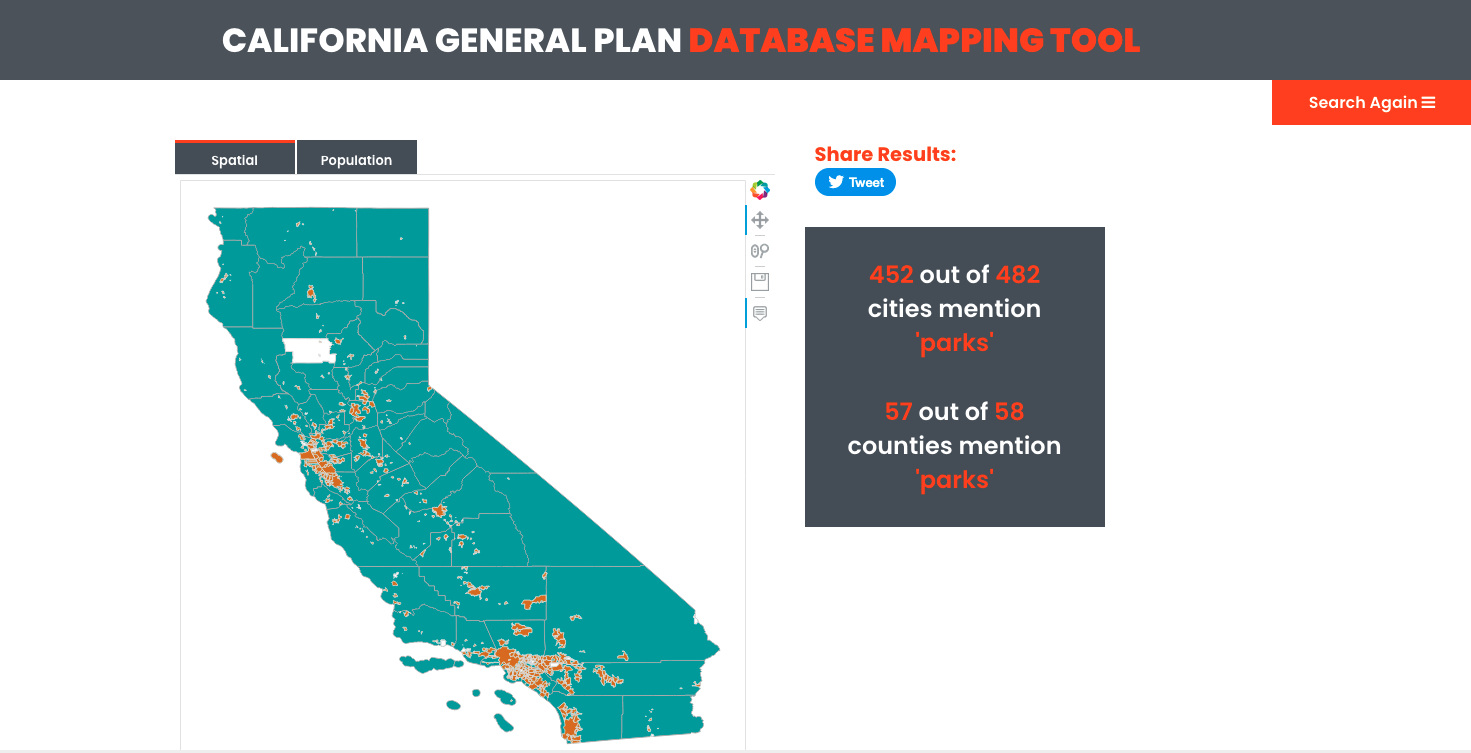

California law requires that each of the 482 cities and 58 counties develop and adopt a general plan, which is a comprehensive long-term plan for the development of those communities. But generally, there has been no one place to access those plans. The new database allows users to look at those plans in one place using search terms.

The new tool was created by a team led by Catherine Brinkley, associate professor of community and regional development and faculty director for the Center for Regional Change. Brinkley said she hopes this tool will give people the ability to better coordinate efforts to solve some of communities’ most pressing issues.

“It is up to all of us to make our cities and counties better,” Brinkley said. “It’s up to us.”

The next step for the Center for Regional Change is to roll out the database to the public by holding community workshops across the state.

First created by students

Brinkley said the site was first built in 2019 by students involved in a campus hackathon, an event where participants rapidly put their coding skills to work. She and other project coordinators have been refining it ever since. On the database’s first page it says in plain language: “Use this portal to access, query, compare and spatially visualize general plans across California’s cities and counties.”

Brinkley hopes that with additional funding and support, they can broaden the tool to include other states.

The purpose of a general plan is to guide land-use planning decisions. Policies contained in a plan guide infrastructure planning to accommodate future growth. The state mandates that each general plan must include seven elements: land use, open space, conservation, housing, circulation, noise and safety. State law requires cities and counties that have identified disadvantaged communities to also address environmental justice in the plan.

“Sometimes plans meet the requirement of what they need,” Brinkley said. “But a lot of California cities go well beyond that because each place is unique, and they have their own desires for how they want to see themselves develop.” Communities often develop bike paths or green trails that can now be, through the database, easily emulated by others.

In the database, users can search for a single term or a phrase. They then can refine searches, and even pop up interactive maps that show the cities and counties searched. Results are also shown in a table that can also be sorted by various categories like jurisdiction name, population or year. From there, users can view a general plan with the highlighted keywords.

Users can search for topics in which they are most interested, and learn how cities and counties are — or are not — handling those issues, Brinkley said. Those working on plans can compare policies or use existing plans as models.

Media Resources

Media Contacts:

- Catherine Brinkley, Center for Regional Change, ckbrinkley@ucdavis.edu

- Tiffany Dobbyn, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, tadobbyn@ucdavis.edu

- Karen Nikos-Rose, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-219-5472, kmnikos@ucdavis.edu