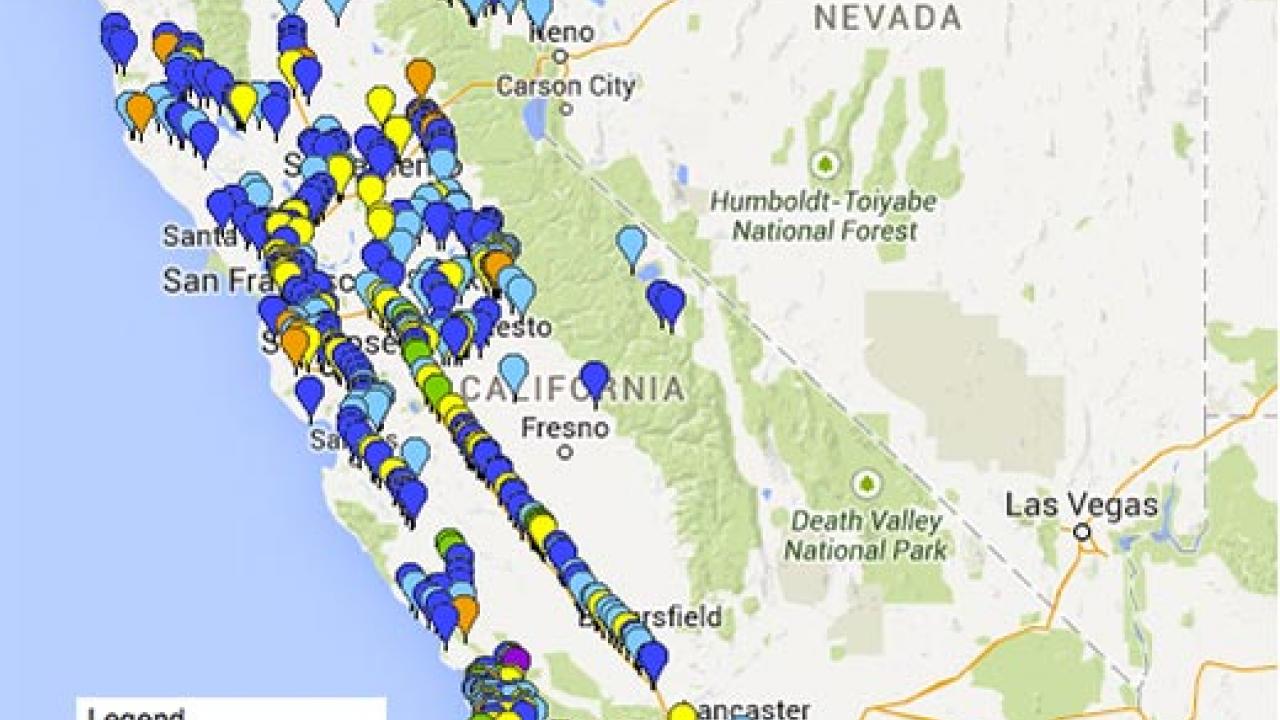

An interactive map shows how California’s state highway system is strewn with roadkill “hot spots,” which are identified in a newly released report by the Road Ecology Center at the University of California, Davis. The data could help state highway planners take measures to protect both drivers and wildlife.

The report describes data logged into the California Roadkill Observation System, a volunteer-submitted database of instances where wildlife and vehicles collided over the past five years. Road Ecology Center co-director Fraser Shilling said it is the largest wildlife monitoring system in the state, featuring more than 29,000 observations of more than 390 of California’s 680 native vertebrate species. The report’s findings cover about 40 percent of the total state highway system.

The data can be seen in detail through the system’s interactive map, which assigns different colored dots for various sizes of species. Clicking on the dots reveals the species — striped skunk, mountain lion, black bear, gopher snake, desert iguana — and where and when they were hit. Species can also be mapped individually. The public can submit entries, including photographs, to add to the map.

“These data help identify places where immediate action is warranted,” said Shilling, who is also a research scientist with the UC Davis Department of Environmental Science and Policy.

‘Rings of death’

The hot spots are stretches of highway the center identified as statistically different from neighboring stretches, taking into account density of roadkill (number of animals killed per mile) and total wildlife-vehicle collisions observed on those highways.

Major hot spots include:

- Sacramento area: Where I-80 and I-5 run across bypasses along the Pacific Flyway, marshy areas attract birds during migration and result in high rates of roadkill.

- Bay Area: “It’s sort of a ring of death around the Bay Area,” Shilling said. Interstate 80 and State Route 101 run alongside the bay, where high rates of wading birds and water birds are killed. Large animals are more likely to be hit on I-280 and State Route 17, particularly near areas of parks and open spaces.

- Southern California: Many areas along State Route 94 in San Diego County have high rates of collisions where the highway runs through wildlife habitat. Shilling said Caltrans is planning to build five new wildlife-crossing structures in this area because the data demonstrate both an immediate need and locations where structures would be useful.

- Sierra: Highway 70 in Plumas County and near Portola has high rates of roadkill, particularly deer.

- North Coast: Both State Routes 101 and 20 show high rates of collision between Willits and Lake Mendocino.

According to Caltrans and California Highway Patrol statistics, there are about 1,000 reported accidents each year on state highways involving deer, livestock and other wildlife. The UC Davis report is intended to help state highway transportation planners develop mitigation to protect driver and animal safety. Such actions could include building fencing and underpasses along priority highways to allow for wildlife’s safe passage.

Drought may increase roadkill

The roadkill observations have led to additional insights, which Shilling said require further research:

- The drought may be increasing the number of roadkill, as animals seem to be putting themselves at greater risk to find food and water sources, crossing roads they may not have in the past.

- While deer tend to use landscape “corridors” when migrating, most other species do not appear to be using them. Landscape corridors, also known as wildlife corridors, are strips of land intended to connect parks and other wildlife reserves. However, the roadkill data suggests that most animals tend to cross where they can, regardless of the location of these corridors.

- Birds are among the most common wildlife group types killed by road collisions. For instance, there is a high rate of barn owl roadkill where I-5 runs through agricultural lands of the Central Valley. Without trees or other elevated structures by the highways, the owls swoop down for prey without considering the trucks and other vehicles coming toward them. In what has not always been a popular suggestion, Shilling recommends for these areas planting vegetation such as oleander and ice plant, nonnative species that repel rather than attract wildlife to the roadsides.

“You have a sterile, dangerous place — the roadway,” Shilling said. “You don’t want to attract animals there.”

Media Resources

Kat Kerlin, Research news (emphasis on environmental sciences), 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu

Fraser Shilling, Road Ecology Center; Environmental Science and Policy, 530-219-3282, fmshilling@ucdavis.edu