Distinguished Professor of Entomology Jay Rosenheim noticed a trend during his office hours a few years ago: Many of his undergraduate students wanted research lab experience but were unsure how to get started. Alongside colleagues Louie Yang and Joanna Chiu, they collectively decided to try something different in 2011.

“Our basic idea was to get students into the labs really early in their undergraduate programs,” Rosenheim recalled. “There’s a whole new set of skills that are very different from what students are typically working on in their formal coursework.”

The Research Scholars Program in Insect Biology, colloquially known as Insect Scholars, aims to provide undergraduates with closely mentored research experience in biology. The program offers 10 to 12 academically strong and highly motivated undergraduates, including third-year transfer students, multiyear research experience that cultivates students’ skills for careers in biological research.

Applications open to enrolled students every January. Scholars are asked to dedicate a minimum of 10 hours weekly to the program. The program’s website notes that insects provide “model systems to explore virtually any area of biology,” creating potential research opportunities “across the full sweep of biology.” This year marks the 12th Insect Scholars cohort with over 110 students completing the program.

Rosenheim emphasized how time is of the essence during a student’s initial attempts at lab work.

“There may be two full years where they’re just learning different methods,” he said. “These hands-on research skills have to be acquired now, and you can’t do it overnight.”

Studying the monarch butterfly and climate change

P.J. Singh is a third-year biology major, loves monarchs and plays trombone in the UC Davis jazz ensembles. After an introductory biology class his first year, Singh received a department email newsletter about the Insect Scholars “and it just clicked with my interest.”

“I really like doing things hands-on,” he explained, “and applying what I learn.”

Singh is currently working with Louie Yang studying ecology, climate change and monarch butterflies. He estimates he spends 60% to 70% of his field research time outdoors at the Pollinator Study Garden at the Western Center for Agricultural Equipment working in a lab with undergraduate and graduate students during spring and summer quarters.

Singh monitors milkweed growths and greenhouse-grown caterpillar eggs used to rear monarchs used in the lab. He takes the caterpillars to the Butterfly Study Garden to observe “their behaviors that they exhibit when they get scared and they drop off plants,” he said.

“We look at climate change and how global warming impacts the species and their behavior,” he explained, with his project analyzing optimal temperatures for rearing caterpillars and survivability as it gets hotter.

Singh’s fall and winter quarters are predominately dedicated to lab and data analysis. He described the research lab onboarding as “a hurdle that you need to overcome” filled with an overwhelming number of steps and processes.

“I was struggling with just reading one paper a week. With the right mentorship, it makes it easier — where to start, how to read a paper, how to look at graphs, figures, and slowly develop your own ideas and projects,” Singh said. “Now it’s a lot more doable.”

Weekly meetings within each lab allowed students, postdocs and lab leaders to present their current projects and research papers, giving undergraduate scholars examples to help sharpen their own lens in the lab. Students are also mentored in grant writing, with several publishing research papers before they graduate, and finding funding for their projects.

“One of the things that we talk about the most,” Rosenheim said, “is ‘how do you choose a question? What’s a good question to choose and how do you choose among questions that occur to you?’”

Singh’s work with butterflies “puts into perspective how all species are important and play a role in ecology,” he said. “No one species carries an environment.”

Singh is still debating graduate or medical school, but his experience with the Insect Scholars program confirmed his interest in fields requiring research and critical thinking.

Documenting California’s insect life

Kaitai Liu is a third-year entomology major whose interest in insects began as a child in Beijing.

“My grandfather took care of me when I was really young,” Liu said, “and he would catch some grasshoppers for me to play with.”

In high school, Liu participated in the China National Biology Olympiad, a part of the International Biology Olympiad, for secondary students in grades 10 and 11. There, he realized, “I really like systematics and taxonomy.” He decided to pursue entomology.

Though he was accepted into a university in China, he chose UC Davis for its entomology department and moved to Davis sight unseen.

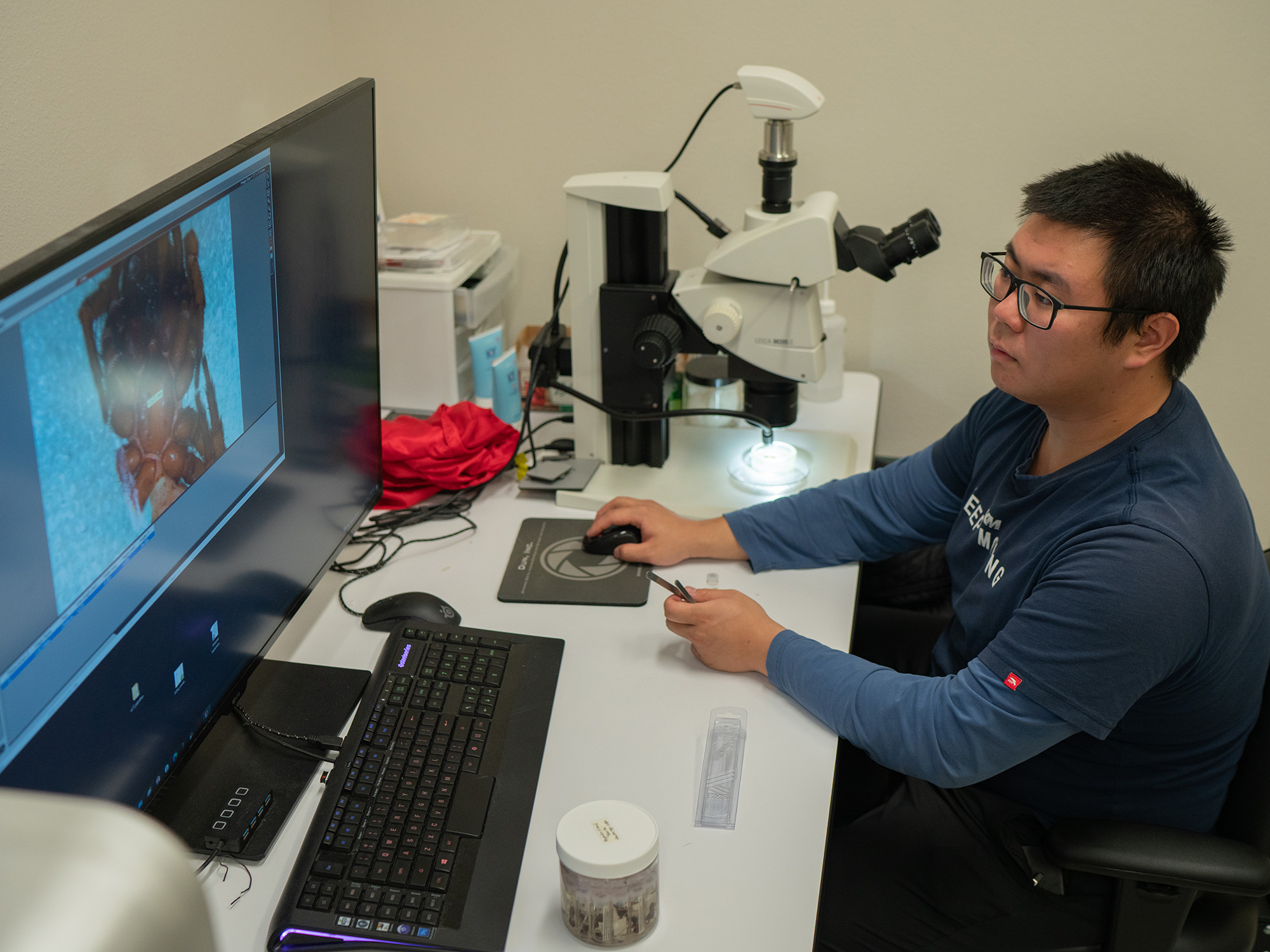

Liu is now completing his second year as a scholar in Jason Bond’s lab, which focuses on the “systematics of spiders” and a project about the reproductive structures of millipedes. Bond’s lab matches Liu’s passion — using systematics and taxonomy to describe and define new species — as well as studying the evolution of spiders and millipedes.

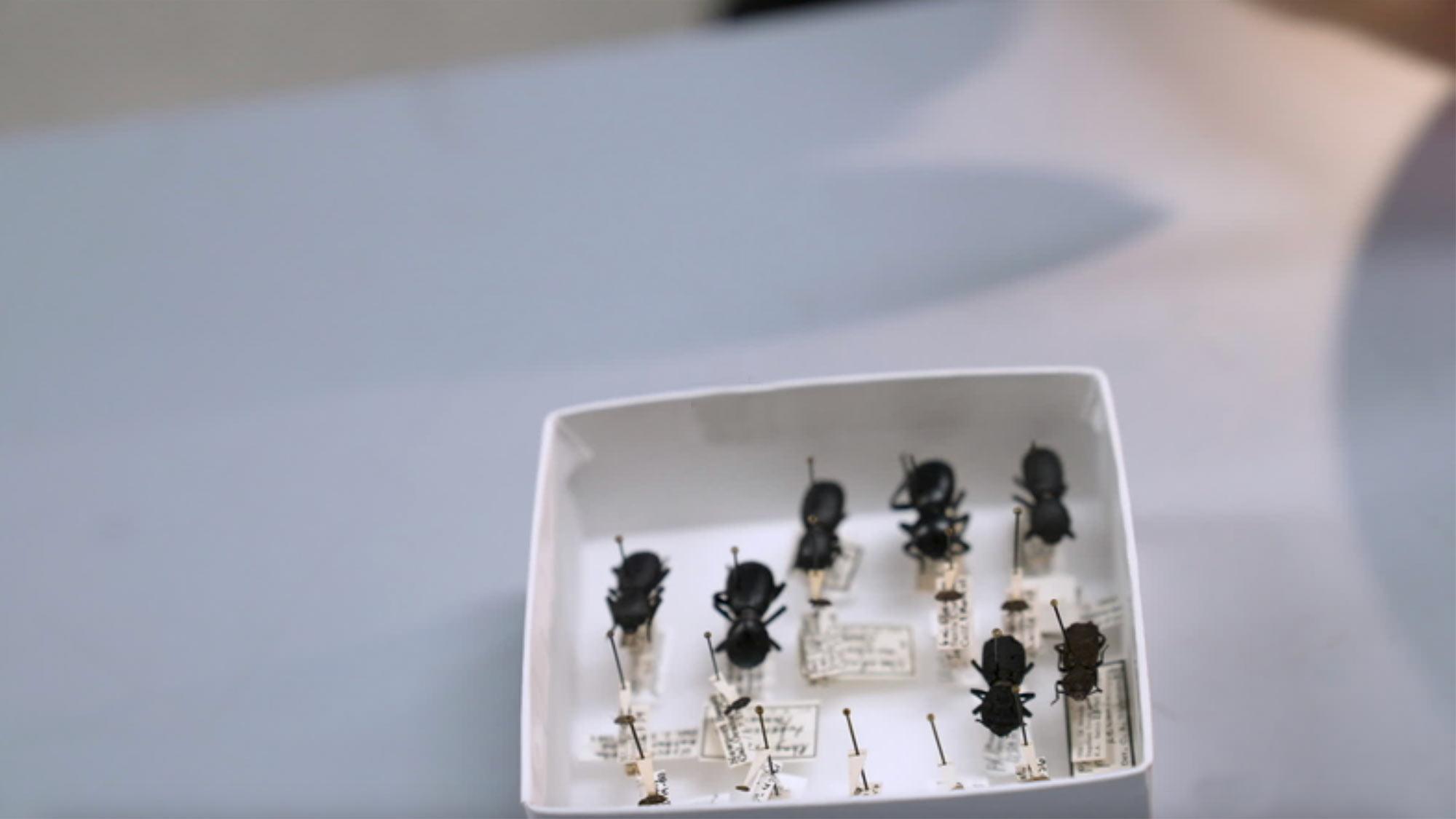

Liu is contributing to the California Insect Barcode Initiative, part of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s executive order around climate change. The state-funded project’s goal is to document all the insect life throughout California. Students like Liu send images and specific insect specimens to the California Academy of Sciences where their DNA is extracted and sequenced. “We can have both the image and their genetic data,” Liu said.

Liu described his lab schedule as flexible, allowing him to balance weekly hourly commitments and academic priorities like midterms or finals. He continues his work in Bond’s lab and the university’s Bohart Museum of Entomology.

“I got a chance to meet with a lot of entomologists and talk to them about their projects,” Liu said, “and get some inspiration from their experience.”

Conducting monarch butterfly conservation research

Ian Jett is a third-year entomology major from Carlsbad, California. He joined Yang’s lab the spring quarter of his freshman year.

“I’ve always been an outdoorsy person,” Jett said, “but I've never really pursued biology until I got to Davis.”

Originally on a pre-med academic track, Jett changed course after seeing a departmental email advertising the Insect Scholars.

“I read through the program, and I just jumped on it,” Jett said. “I thought it would be a good opportunity to start getting hands-on lab experience.”

Jett assists Yang’s lab with monarch conservation, helping to rear monarch caterpillars in the greenhouses for future controlled experiments and observation. The caterpillars’ food levels and lifecycle stage were also recorded daily. Jett also ensures their optimal temperatures, including a particular caterpillar who required “four different fridges at different stages in their life.”

Jett’s first self-designed project took place at the Pollinator Study Garden, where multiple labs use at least 15 plots, or wards, for research. Within these plots, Jett explained, were different species of milkweed that attracted honeybees eager to collect nectar and pollen.

But there was a literal catch.

“Honeybees tend to get stuck in the flowers due to the flower anatomy; they can’t get out and end up dying on the plant,” Jett said. “I was looking at what the effects of dead honeybees on the milkweed flowers had on other pollinators, to see if they would avoid the flowers or not, or how other honeybees would react behaviorally.”

Jett would visit the wards multiple times a week and prepare pairs of plants, ones that did not have a dead honeybee and ones where Jett planted a carcass himself.

“I would take 10-minute videos of the plants to see if the frequency of other honeybees visiting the plant was changed based on the presence of the dead honeybee and the effect the carcass had on other insects.”

Jett collected over 20 hours of footage, noting the number of honeybees who visited and other insects present. Describing this initial experiment as “surface level,” Jett identified additional layers to study more in depth this summer, including insect-plant relationships, social systems and impact of pollinators.

“You have to take initiative because it’s like an independent kind of program,” Jett explained. “It’s on you as the student to reach out and ask people in your lab for help.”

After meeting faculty and other students, Jett changed his major to entomology and is considering grad school. He plans to stay in Yang’s lab and then pursue conservation work with organizations like the National Park Service and continue research into the biological control of invasive species.

“My career should be something that I’m happy doing, something that would allow me to be more outdoors in my career,” he said. “Interacting with the environment and getting involved in conservation resonated with me.”

What Can You Do With an Entomology Degree?

Interested in insects? Obsessed with bugs? Consider a career in entomology. Here is everything you need to know about the entomology major at UC Davis.

Media Resources

Media Contact:

- Amy Quinton, News and Media Relations, 530-601-8077, amquinton@ucdavis.edu